By Jose Kavi

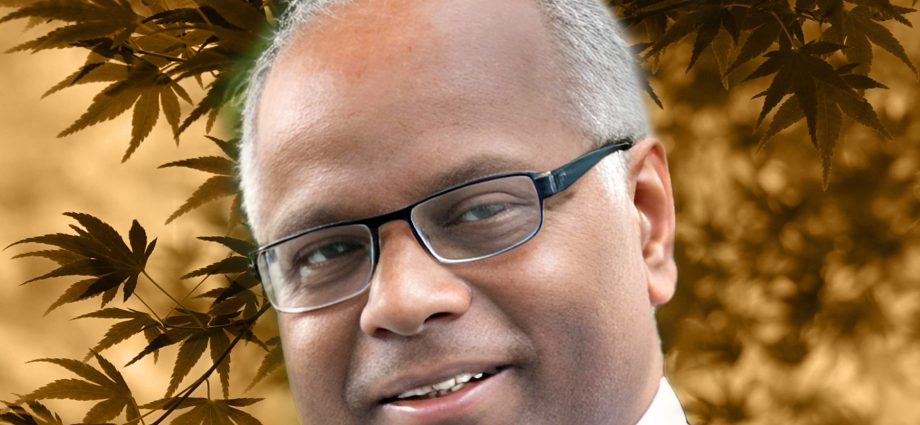

New Delhi, March 18, 2024: Father Paul Thelakat on March 15 stepped down as the editor of the Sathyadeepam, the largest circulated Catholic weekly in Malayalam language. The 75-year-old priest of the Ernakulam-Angamaly archdiocese edited the weekly for a record 37 years.

So, on March 13, the cultural and literary society in Kochi, where the priest is based, turned up to honor him, who has been a regular presence in its cultural evenings.

At the program, M K Sanoo, 97-year-old revered writer of Kerala, hailed Father Thelakat as someone who has achieved immortality through words, writing and philosophical thinking.

On the occasion, an autobiography of Father Thelakat titled “Kathavasesham” (The Story After) was released.

Father Thelakat, who now lives in the archdiocese’s priest home, shares with Matters India about his life and works.

What are your thoughts as you step down from the editorship?

Editing an English news and views paper at this age is challenging. You cannot force your body beyond its stretchable limits. I could do it only because of disciplined life and the consuetude of doing the work for many years. But one cannot go on indefinitely. I enjoyed the work; it was challenging and creative.

When did you take over as the Sathyadeepam editor?

In 1986, after I returned from my studies in theology and philosophy from Leuven, Belgium. Even during my seminary days, I used to write and edit. I was fresh and young when called to take up the diocesan paper that reached entire Kerala. I accepted the job, with no experience in journalism.

I went to Deepika and the chief editor of the daily newspaper arranged my stay with journalists who showed me the making of the daily. Sathyadeepam carries news and views for the ordinary Malayalam reading Catholics. I made a small change. Along with the views of the so-called writers I published the thoughts of ordinary Catholics with some knowledge of journalism in the weekly.

I also interviewed people who matter. Two staff would interview and write it for the paper. This ignited interest in the paper. Hard work and study of persons and issues also helped. We asked pertinent and important questions on an issue to stakeholders.

Disturbing questions produce enlightening responses.

Looking back, what were your challenges?

The challenge was to have the courage to ask questions. The answers will follow. Very often we do not dare to seek. The key to good journalism is the capability to raise questions to society and the Church and elicit answers.

One challenge I faced was from some priests who objected to the publication of news about scandals within the Church that have already appeared in international Catholic media. They asked me to publish only good news. The Bible is Good News, but it contains a lot of scandals, sins, war, prostitution, betrayal and what not. Good News is not news about good things. What makes it good or bad is how one writes it. An incident could be narrated as good news or bad.

Did you get support from the Church, your superiors and others?

I had no problems with my superiors, I was always in the presbyteral council of the archdiocese, very often I was a member of the college of consultors, I was the Presbyteral Council secretary for two consecutive terms. The official Church supports the paper and its policies. It is not just a diocesan paper; but a paper for all Christians. As an editor I believed in collaborative work.

What prompted you to start an English edition of the Sathyadeepam? Did it help you to reach out to people outside Kerala?

There were two reasons. First, the lack of a good publication in English with Catholic news and views. Second, drastic demographic changes arehappening in the Syro-Malabar Catholic Church. The Catholic population in Kerala used to be agrarian with rural settings. Now it is a community of educated professionals migrating to more urbanised places.

Catholic youngsters are increasingly migrating to the West and other developed worlds. The sedentary village life has given way to fast moving globalized world. As English education gained popularity, Malayalam has become a local language. We needed an international language. The Church communication has to gear up to meet such changes. Moreover, Cardinal Varkey [Vithayathil] was keen to start the English paper.

You have been a prolific writer. How do you find time for that in your busy life?

I am interested in two subjects — literature and philosophy. My faith and my values need articulation and literature and philosophy give me the language to express myself. I believe that the capability to ask questions and seek answers is the key to any intellectual life; so also, in good journalism.

You are respected as a man of spirituality by people from all religions. How did you reach out to people of other religions? What were the challenges?

My mother used to scold me for crossing the borders. She wanted me to live within the accepted confines. It is true I crossed many borders. The crossing was to know the other side. I have participated in temple functions, gone to mosques and masjids. I have given talks to the Congress Party meetings and the Marxist gatherings. I have participated and talked in many literary meetings. I have taught on Greek tragedies and done critical studies of many Malayalam and foreign novels. Only if you travel beyond your fence, will you be able to find truth and beauty on the other side. Once you see both sides you can never be a fundamentalist. You also understand yourself better.

You have been critical about the Church leaders’ political clout? How does it affect the Church?

I became critical of the Church leaders in my ripe old days. Cardinal George Alencherry [former head of the Syro-Malabar Church] accused me of being a Marxist and misleading [his predecessor] Cardinal Varkey. The one who accused me of being a Marxist himself had the metamorphosis by seeking political clout from the Marxist Party. There is the danger of burying your soul for the party.

I see [Church leaders’] political liaison with the Left Front government led by the Marxist Party and its police force in Kerala and the BJP [Bharatiya Janata Party] at the centre. You saw [the cardinal] offering Mass on Maundy Thursday in [St Mary’s Cathedral] with police force both inside and outside the church. My criticism was more radical, especially when I saw the Church leadership losing its moral authority. Criticism is comparing what is with what could be. This critical consciousness is the moral or value orientation with time and space. It is a prophetic charism we live with.

You were involved in some controversies such as forging documents. How did it happen? What is the truth?

It is in court, so I have limitations of speaking about it. It is true that I did receive some documents and gave some of them to my immediate superior Bishop Jacob Manathodath. I gave them only to my superior, not to any media or the public.

What about the liturgical dispute?

Liturgical dispute was unnecessarily created in the Church. It was a decision in 1999 when Cardinal Varkey Vithayathil was the Major Archbishop. However, the decision could not be implemented because of resistance from the ground, first in the Trichur archdiocese and then in Ernakulam. The decision was to make uniformity, but it destroyed unity.

Is uniformity such a great ideal? Pope Francis in his speech in Paul VI Audience Hall on October 31, 2014, said, “Uniformity is not Catholic, it is not even Christian. Rather, unity in diversity.”

From a theological point of view, there are only two orientations, face the East or face the people. The Mass is purely a ritual in language; it is not a monological language but a ritual in dialogue. The face of the other is the epiphany for Emmanuel Levinas [1906-1995, a French Jewish philosopher]

To turn to the East was the command of Emperor Constantine. Turning to people was applicable not only to the Latins of the West but to the Easterners. The Chaldean Catholic Church permits both options. Moreover, the way the Synod decision was reached and implemented betrays the use of cunning rationality and nonfactual reporting.

Please tell us something about your family, schooling and seminary training.

I am from an agrarian village. The villagers were neither poor nor rich. My early life involved cultivation and harvest, and both demanded hard labor. Our land was cultivated thrice a year. During the intervening period we made mats with bamboo collected from the forest. This gave us some money power.

I completed my schooling amid work in the field and making handcraft. I passed matriculation with a star over my number — first class. Two things used to frighten me, darkness and the poisonous snakes. But the sky always enamoured me. Any time in the night I could look to the sky and locate stars and know the time. I always look up to the stars and my worries just disappear.

We are four brothers. My elder brother helped my father. I, the second, assisted my mother. This helped me learn what women do at home and in the field. I learned to cook and serve the workers of our land. I also learned what is done by women in agriculture — planting, weeding, harvesting and the like.

One last question. What is your future plan?

I am a man of hope amid troubles; I look for a better future. The future tense is a great invention of man. As the son of a farmer, I always look to the skies for the stars. A farmer always hopes that the soil and the sky will bless him with a good crop.